Anonymous’s Story

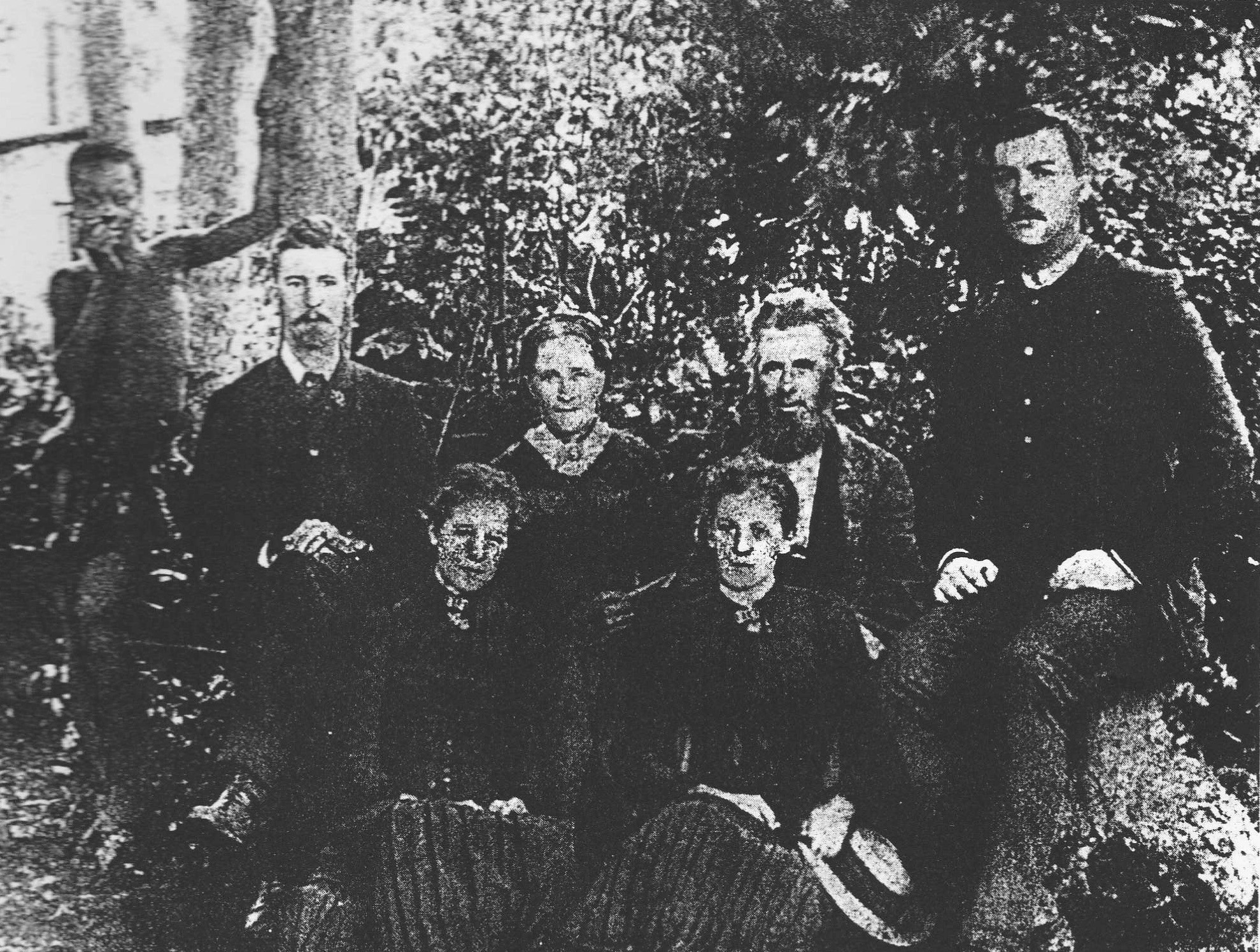

In 1880, my maternal great great great grandparents, Joseph and Anne Neden, left their comfortable life in Manchester with their four children and relocated to South Africa. They had been sold the promise of a better life, one filled with opportunities and financial rewards for those willing to work hard. The challenges of tilling the soil, where fleshy red aloes make a mockery of the parched earth underneath, went unremarked and my ancestors were woefully unprepared. According to family mythology, Anne never recovered from the disappointment of it all. Life in Africa was so different, raising children in this new environment, where infrastructures--homes, churches, hospitals and schools--all still had to be built was tough. Nevermind whether the colonial endeavour was legitimate, which history has clearly shown it was not.

Fast forward to 2000 and this white South African, having recently graduated from university with a seemingly dead-end degree in the humanities, seeks opportunities elsewhere, much like her ancestors did 120 years before her. In post-apartheid South Africa she is not black enough. Her whiteness represents racism. It doesn't matter what she really thinks or feels. This is a country where life has been governed by appearances for too long and will continue to be. She is African. African blood may not course through her veins, but African soil is embedded under her finger nails. This is home. The only one she has ever known.

But opportunities for young white people with seemingly self-indulgent degrees are sparse. It is time to look elsewhere. England, with its grey skies and stoic population, is not the first choice, but rather the only one. I resign myself to being anonymous huddling under an umbrella joining the drudgery of society shuffling out of the tube stations, until my working holiday visa request is denied. The reason given? I stated on my application that I wanted to work in London and use it as a base to explore the rest of the UK and Europe. I hadn't realised that one of the conditions of this visa was money earned in the UK had to be spent there too.

A passport was blacklisted. A passport was lost. And the twists and turns of life led me to New York instead. After a two-year long-distance relationship with a man living and working in London, I tried again. This time with the costly assistance of an immigration lawyer. With two further degrees and some work experience to my name since my last failed attempt, it turned out I wasn't much more attractive to the British authorities than I had been before. The immigration lawyer suggested we get married. Fortunately that was our intention anyway and we simply fast-tracked our plans, marrying quickly and quietly in a tatty old court house. I remember as we were leaving my partner's family home, my mother-in-law tipped the contents of her hole punch into her pocket, which she threw over us as we left the court surrounded by strangers queuing to pay traffic fines. We had said we didn't want a fuss, to save the celebration for when we could pay for a 'real' wedding.

Life in London was hard and frequently lonely. My bones cold from the damp weather warmed only by a deep love for the man who lured me here. With time I came to like England, paying regularly to extend my visa, obsessively logging the days spent out of the country to ensure I qualified for indefinite leave to remain and taking the ridiculous Life in the UK test, all to ensure my children's rights to live here. South Africans call those who leave Ex-South Africans. Might this be the only nationality to be disowned in this way? Thirteen years have passed. In another ten, I will have lived in England longer than I did in South Africa. Will I ever feel English? Unlikely. But I am not South African any more either, if I could ever have claimed to be. I am one of the increasing number of disconnected, uprooted and yet somehow interconnected international citizens.

A colleague recently told me we should talk about migration not immigration. As a German he had simply decided to relocate. Immigration has become a contested word. However, abandoning it does not neutralise it. I did not migrate. I immigrated. I sometimes wonder whether my ancestors ever thought the decision they made in 1880 would continue to have an impact on their descendants today?

-Anonymous, London